YouTube Companion Video

Introduction

The future of pitching isn’t just deeper arsenals, but more deceptive and optimized ones tailored to player needs. This study seeks to answer the question: What is the future of pitching? I will give background throughout the article to set up my future points, all leading to the end of this experiment, where I will give my best recommendations for what I think the next step in pitching might be. This was not a solo journey, and I greatly appreciate Lance Brozdowski, G.G., Collin Murray, Kick Dirt Baseball, and my Prospects Live family for their help and support in fleshing out my ideas. With that being said, I hope you enjoy!

Arsenals

Background Info

Before we get super in-depth with all the topics I want to cover, I want to give some quick background on pitch arsenals. Feel free to skip ahead to the more interesting stuff if you wish. 139 pitchers have thrown 1,000 pitches this year as of July 22nd. The average qualified starting pitcher has 4.47 pitches in their arsenal. Here’s the breakdown:

Please excuse my ChatGPT-generated graphs; my technical skills have not quite caught up to quick graphic creation. As you can see, the world now revolves around sinkers ever since seam effects became a well-researched topic. Now, let’s dive into some splits. The average right-handed pitcher throws 4.55 pitches, just slightly more than average, which makes sense. Spoiler: There are no major breakthroughs in this section, just some light background information to ease you into the latter parts of this article.

Now, what if we look at only the best pitchers in the MLB? I had a feeling coming into this study that better pitchers throw more pitches, I think they call that a hypothesis. When filtering to only the top 5 right-handed pitchers by xFIP, we find that they throw 4.8 pitch types on average.

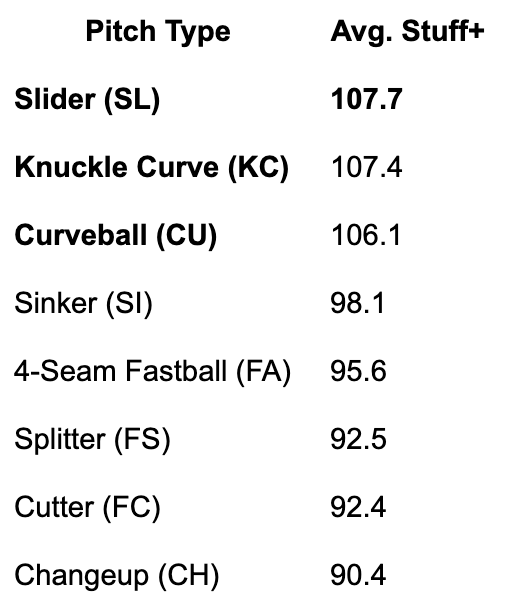

Looking at the information presented, it appears as if the best right-handers use more pitches than normal, while also relying on… curveballs? I thought curveballs were dead? They also all appear to favor splitters over changeups.

Now, looking at lefties, we see that they have to throw fewer pitches than righties, averaging 4.2 pitches per arsenal. This makes sense due to the baked-in unique look that lefties have since they are rarer to see.

But, just like the top righties, the top 5 lefties in the league throw 4.7 pitches on average, showing that the best pitchers currently in the MLB have nearly 5 pitches in their arsenal. The best lefties also appear to favor changeups over splitters, while throwing more sinkers than the typical lefty. We won’t read too much into this because it is a small sample size, and every individual pitcher is inherently unique.

Bad Fastballs and Stuff+

Now that we’ve done some quick arsenal research, let's have the stuff debate. People hate Stuff+ models apparently, which is fine; they’ve probably gone a bit too far. Most + models are diving into freak territory, but that doesn’t mean they don’t have their value. As a heads up, I am using OG FanGraphs Stuff+ for all of my future stuff talk. Let’s just do some quick math stuff now, proving why Stuff+ matters in the first place.

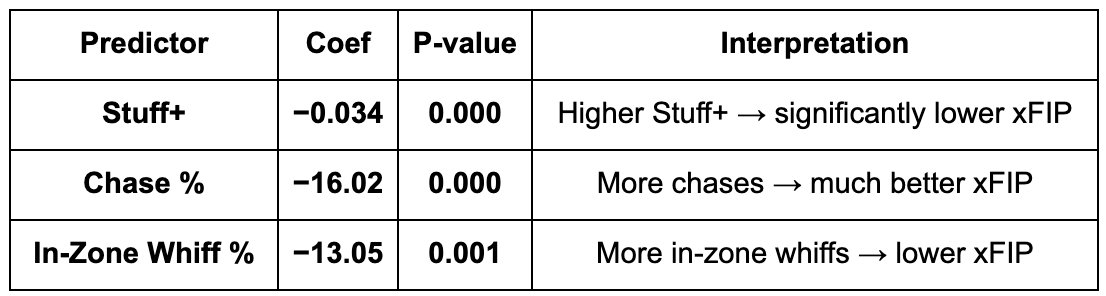

Running a multivariate regression as seen below to predict xFIP ended with an R value of 0.5, which explains 50% of the variation in xFIP. While pitching can’t be quantified in one or two stats, xFIP and Stuff+ are pretty good ones to look at.

In simple terms, better stuff+ predicts a significantly lower xFIP, and to further prove that better Stuff+ leads to more Chase and in-zone whiffs, which are also both great predictors of xFIP

A trend we often see with stuff models that I want to touch on first is the bad fastball resulting in bad pitchers. Obviously, the fastball is the easiest to control pitch, making it the pitch that pitchers are most comfortable with, in general. Because of this, pitchers throw a lot of fastballs (groundbreaking stuff, I know). But what if your fastball is inherently bad in regards to stuff? Well, here’s an example of 5 good pitchers that have really bad 4-seam fastballs based on stuff grading.

Clay Holmes, 5 pitches. 7 % FF Usage (74 stuff+)

Jose Soriano, 5 pitches 8% FF Usage (81 stuff+)

Framber Valdez, 5 pitches, 2% FF Usage (83 stuff+)

Sonny Gray, 6 pitches, 21% FF Usage (85 stuff+)

Ranger Suarez, 6 pitches, 14% FF Usage (84 stuff+)

All of these guys throw 5 or 6 pitches, which makes a lot of sense. Pitchers still need controllable pitches, so all of these guys throw a cutter, sinker, or both to give them an easy-to-command pitch that isn’t their bad 4-seamer. The majority of the guys above actually use their 4-seam fastball as a setup pitch at the top of the zone, allowing them to then use their breaking ball more effectively.

Sonny Gray has slowly been decreasing his 4S usage as it has gotten worse, throwing it primarily to lefties on the outer half to tunnel with a cutter. It’s important to note his fastball has a 3 RV despite its low stuff+, showing how good pitchers work around bad fastball shapes.

The vast majority of guys with bad fastballs, according to Stuff+, are… struggling in 2025 to put it nicely.

Having a good 4S does not simply align with velocity, or Jose Soriano would have a better fastball metrically. Having a good shape matters and allows for better pitch tunnels. The five guys we just discussed are the exception because they have multiple plus secondaries to rely on.

More Pitches = Better?

This brings us to our next discussion: Does throwing more pitches give you better results? Let’s take a look at xFIP versus arsenal depth.

Okay, so no, having a bigger arsenal doesn’t exactly mean you’re going to get better results. More pitches might suggest slightly better performance, but nothing definitive. This was expected; there are a lot of pitchers in the MLB, and if a trend like this were clear, more people would be talking about it.

Let’s take a look at some graphics that compare xFIP and Stuff+ to arsenal depth now.

To further muddy the water, among qualified starting pitchers, those with fewer pitchers had a better xFIP and better Stuff+. We can assume the Stuff+ result because guys with bigger arsenals can’t throw 6 elite pitches. The main reasoning for more pitches equaling a worse xFIP is likely the previous trend we talked about, where pitchers with bad fastballs have to throw more pitches, but those that do have bad fastballs tend to have worse results overall. A good fastball is still the key to unlocking success in pitching.

Arsenal Takeaways

-Having more pitches doesn’t mean they’re effective.

-Some people have to throw more pitches out of necessity, for example: bad FB, pronator v supinator, etc.

-Dominant 2 pitches that play off of each other are a great starting point.

-Reactionary reasons need to be considered: Pitchers might add more pitches when they are struggling versus succeeding.

-Stuff+, tunneling, and command matter more than arsenal depth.

Despite some pitchers' deep arsenals, many are not performing well. This dataset applies to roughly 25% of pitchers with deep arsenals. These are your guys, like Kyle Hendricks and Miles Mikolas.

In the end, stuff is still king. There are no clear overall findings within pitcher arsenals in terms of the future of pitching, but there are several takeaway points we will talk more about at the end of this article.

Pitch Types

Fastballs are better than ever, but they’re being thrown less than ever before. Why?

Fastballs get hammered. Hitters slug more versus fastballs than any other pitch, and they are basically straight. The best fastballs, when thrown in the most optimal spots, can be elite, but in general, it’s hard to get away with a fastball-heavy approach as a pitcher.

If you don’t have an elite fastball, you have to add more pitches to your arsenal to get by, but we just proved that, so let’s shift the focus here.

Now more than ever, having multiple fastballs is important, and honestly, throwing all 3 is probably best. Having a cutter and sinker gives a pitcher access to controllable, high velocity pitches that allow them to decrease their 4-seam usage, while making their 4-seam fastball, in turn, play better than its Stuff might indicate through concepts like tunneling and pitch decay.

We see a lot of elite pitchers use their 4-seam fastball as an equal primary pitch or a secondary pitch nowadays. Tarik Skubal, the best pitcher in baseball, is simply a great example of this.

First of all, Skubal knows his advantage as a hard-throwing lefty, and his pitches reflect that, with the second-best pitch in the league according to run value being his changeup

Because of this, Skubal throws his changeup as his primary pitch at 32% of the time. Behind that, his two fastballs are his secondaries at 27% for the 4S and 25% for his sinker. Tarik also understands his platoon pitch advantages, dialing up more changeups and 4-seamers versus righties, while transitioning to 40% sinkers, and 20% changeup/slider against lefties. Skubal's changeup is so good that he only needs two pitches to get righties out consistently, while maintaining the threat of throwing the rest of his arsenal. Against lefties, Skubal prioritizes sinkers and sliders more, which both have the same handed platoon advantages.

The Boston Red Sox

Yes, the Red Sox get their own category here because they began zigging when others were zagging or slowly zigging. The Red Sox consistently look to acquire players with good four-seam fastball shapes, which makes a lot of sense. However, the Red Sox throw more breaking balls than any other team in the league throughout their organization. How does that make sense? Well, maybe four-seam fastballs aren’t the future of pitching optimization; according to the Red Sox, the future of pitching lies in breaking balls, which gives us a hint toward what organizations might be thinking the next trend in pitching is. Using good fastballs as a secondary offering or shared primary offering could help defend against pitch decay, while also forcing pitchers to throw their best stuff offerings more despite a downtick in command. Good fastball shapes are also one of the more platoon-neutral pitches in the game, allowing pitchers to increase fastball usage toward opposite-handed hitters, while throwing way more breakers in platoon-favorable matchups. When a team goes all in on breaking balls, it denotes that they are less worried about location and more worried about stuff.

Now that we’ve established four-seam fastballs don’t need to be your primary pitch, let’s keep going down this road of pitch types. The next question is, how do you round out an arsenal? I want to share a quick personal story about my own baseball career before getting any deeper into this, bear with me here.

Pitching Experience in Pronation and Supination

I was a superbly average college pitcher. If you looked at me in a bullpen, though, you would question if I ever even played baseball.

I topped out around 83 mph in game by senior year this past Spring, after getting 2 elbow surgeries on my elbow and ulnar nerve. After those surgeries, my arm anatomy changed, and so did my pitch repertoire. Previously, throughout my baseball career, I was the definition of a pronator. I had a great changeup, with a lot of arm side movement, and threw a 100% spin efficiency fastball that lingered around the deadzone. I was a decent player before my surgeries, but I was never great and rarely collected strikeouts.

One interesting thing with elbow surgeries is they can really limit pronation post-op, and I returned rather quickly from my second surgery in order to play my senior year, to the point of not being able to fully twist my arm to the outside of my body. This anatomical problem led me to become a supination-biased pitcher for my last season of baseball, training my body to cut everything I threw. You can’t just wake up one day and become a supinator, so realistically, I could neither supinate nor pronate at a high level, but during this season, my only shot at playing was to start spinning the ball as much as I could.

Because of this turn of events, I am one of the rare pitchers, likely in the world, who has been both a supinator and pronator at different times in my career. I wouldn’t recommend rushing back from elbow surgery to play baseball, but it has given me this unique perception.

As a pronator, you are extremely limited in your ability to throw breaking balls hard. It is possible to get big movement from a pronation background, but it will be at the detriment of velocity. It is also much harder to achieve a true ride fastball by cutting the ball slightly. Since velocity is king, even on breaking balls, pronators simply have worse breakers than supinators do. This limits the amount of high-potential pitches a pronator can throw, as they often do not access seam-shifted wake, which can open up an arsenal.

Supinators, on the other hand, have endless pitch type options due to their ability to cut a baseball with a certain grip, inflicting seam-shifted wake, allowing them to round out a pitch movement plot much better than pronators can. When I made the transition to supination, I added 2 extra pitches, my fastball became better, and my ERA as a result was cut in half. I cannot overstate my firsthand experiences and how they have led me to believe that supinators are ‘superior’ in pitching.

For fun, here’s a video of me pitching for Bushnell University in Oregon, where I now coach. Mind that the camera angle messes with perceived horizontal movement on video. I had never been able to access these kinds of pitch shapes as a pronator, getting far more overall movement on my stuff. I was now able to throw my fastball as an out pitch up in the zone due to my newfound vertical movement, as well as access a wider horizontal movement spread in my sinker and slider. I was not able to seam shift a changeup as easily, so I went with a kick-change in my senior year, which played near 0 vert.

Pitch 1: Slider, Pitch 2: Sinker, Pitch 3: Changeup, Pitch 4: Changeup, Pitch 5: Curveball, Pitch 6: Fastball

This change in my pitching career based on supination and pronation is the basis for this study being created in the first place. I have thoughts on both and how to maximize them, but overall, supinators are at a distinct advantage in the pitching world.

Why Cutters Matter

One of the easiest ‘quick fixes’ to an arsenal is adding a cutter. While this is not a new idea, I believe it is still important to this conversation. Back in 2022, Ethan Rendon, Elijah Emery, Will Sugar, and Tieran Alexander published the first public pitch tunneling study at Prospects Live. It can be found here. Pitch tunneling can help an arsenal play up from stuff ratings, while also being a key explanation for why good pitches are not performing well in-game. The most usable tunnel is between fastballs and sliders, with these specs needed to properly tunnel the two pitches:

-Horizontal separation between 6 and 14 inches

-Vertical separation between 8 and 16 inches

-Velocity separation between 6 and 11 mph

While we haven’t gotten to our section on sweepers yet, pitch tunneling is a key factor in why sweepers perform worse than other, tighter breaking ball shapes. In a vacuum, sweepers are great, but they can only perform great in-game given proper arsenal context.

Let’s take a look at JP Sears, a LHP for the Athletics. Sears’ numbers are well below average, but he throws one of the best sweepers in baseball. In fact, it’s the third-best sweeper in baseball with a 9 run value and elite stuff grades.

Here’s the problem, though. Sears' pitch mix does not allow this sweeper to play as well as it should. While the lefty sweeper will never perform as well in-game, Sears gets far worse results on his sweeper in-game than any of the other top sweeper guys in the MLB. Why is that? Well, there’s a 24-inch horizontal separation, and only a 7.5-inch vertical separation between his sweeper and four-seam fastball. That is what we call an untunnelable pitch. J.P.’s slider isn’t bad per se, but it also does not do an effective job at bridging the gap between his fastball and sweeper, playing too closely to his sweeper shape. Righties are having a field day versus Sears because he throws 60% four-seam/sweeper against them, but there is no deceptive interaction between those two pitches, especially since the sweeper plays worse metrically against righties. Instead of throwing a mediocre slider, what if Sears threw a hard cutter?

Tunneling

First off, the cutter would give a great velocity median between his fastballs and his other pitches, likely sitting in the mid to upper 80s. Next, the cutter would ‘bridge the gap’ between Sears’ fastball and sweeper, allowing both of them to play better. Don’t just hear it from me, though. This is what the tunneling study has to say about cutters:

“Most of the players with an extreme deviation in their horizontal movement on the fastball and slider who still find results have one thing in common: they throw the cutter. In fact, half of the sliders in our dataset that have over 17” of horizontal separation from the primary and still get chases 35% of the time pair with a cutter. Cutters are the living miracle that make sweepers usable and tailing two-seamers effective as well. The purpose of a cutter is to split the plate and bridge extreme gaps in both vertical and horizontal movement between a fastball and slider.”

Adding a cutter to Sears’ profile would also allow him to stop throwing his sinker versus righties, which currently has an opponent batting average of .563 when thrown to righties. The cutter will also allow him to continue throwing his sweeper to righties despite its platoon disadvantage, leaning into what Sears’ strengths are.

This isn’t just a Sears problem. 50% of starting pitchers have a sweeper in their arsenal, with a solid amount of those pitchers not having a cutter in their arsenal. While big horizontal pitches can get great results and limit damage while increasing whiff, those stats are only reachable by having pitches to bridge horizontal gaps.

After learning all of this information, a fair assumption is that pitchers who succeed while only throwing 3-4 pitches have great tunneling between their pitches. I’m on a bit of a tangent here, but there are only 9 pitchers who throw only 3 pitches > 5% of the time, with those being: Dylan Cease, Jeffrey Springs, Kevin Gausman, Tyler Anderson, Jack Flaherty, Cristopher Sanchez, Jacob DeGrom, Chris Sale, Lucas Giolito. The first thing that jumps off the page is that the majority of these guys are above-average starting pitchers. They are what we would call outliers in the conversation of expanding arsenals.

But why are they outliers? They all tunnel their pitches INCREDIBLY well. In fact, Tyler Anderson and Kevin Gausman are two of the most popular names in the tunneling movement of recent years. Let’s pull the numbers on one of the greatest pitchers of all time, Jacob DeGrom, who is still succeeding with an elite fastball-slider tunnel with an optimal changeup (changeups all tunnel, but in different ways than other pitches).

Well, there you have it, all of Degrom’s pitches are within optimal movement patterns for pitch tunneling. While DeGrom still has elite stuff, he also has optimal tunneling on all of his pitches, giving them an extra layer of deception. This deception allows DeGrom to use only 3 pitches regularly, which is an available option to elite tunnelers. While there are obviously outliers within our dataset, like Chris Sale, the majority of these pitchers have pitch movement that allows for great tunneling.

Rounding out an Arsenal

We’ve established the differences between pronation and supination, but what is the ultimate separator? A combination of shape and velocity. In order for a pronator to throw a large sweeping slider, they have to force their wrist angle and fingers to the outside of the ball, an unnatural movement for a pronation-biased pitcher, resulting in a slightly reduced velocity on their breaking balls. While this is not the case for everyone, and some pitchers can fall in the middle of pronator versus supinator, it is a real problem for a large number of pitchers. The inability to access movement to the glove side without sacrificing velocity becomes a significant hamstring for pronators to have a starter's arsenal. A great example of this phenomenon is Logan Henderson.

Despite an average arm angle, Logan Henderson can barely move the ball across the zero horizontal line when pitching, with his cutter and slider having poor shape and ‘stuff’. Henderson, as you can see by his ridiculous changeup, is a supreme pronator. His fastball is efficient, and with his arm slot and high locations making him able to get good vertical movement on the pitch consistently. After those two pitches, there isn’t much going on for Henderson. If he tried to gain more horizontal movement on his slider, his velocity would drop even more on the pitch, despite it already being ~10 mph off of his fastball, which would not be a viable pitch. It is important to note that there is very little Logan Henderson and the Brewers can do about these problems. Information on how to negate pronation and supination biases is still in its infancy, but I would imagine the Brewers have their own plans for engineering another quality pitch or two out of Henderson.

Here, for example, are the hardest thrown sliders in the league. The majority of these pitches get much more movement than Henderson’s, while being much harder and being closer in velocity to each pitcher's fastball. The balance of movement + velo + separation is a large part of what creates a successful secondary offering.

Supinators can’t just throw the breaking ball better, though; they can leverage seam effects to garner more pitches that move to the arm side, such as sinkers and changeups. If a supinator has a hard time throwing a traditional changeup, they have plenty of other options to get into a similar area on a movement plot. The aforementioned seam-shifted changeup, the kick-change, and the splitter are all viable options for supinators to tinker with. There is little excuse for a supinator not to have a quality 4+ pitch mix. Fastballs with a slight cut to them also generally tend to get better vertical movement.

In 2025, offspeed pitches are on the rise, thanks in large part to splitter usage increasing, especially in right-handed pitchers. The reason righties should throw splitters is that they are more platoon-neutral than traditional changeups, giving them viability against both sides of the plate, thus increasing arsenal depth. I could talk more about splitters and their uptick, but the overwhelming point is that it’s simply a better pitch for most players to throw.

In regard to the new ‘fad’ of the kick-change, it gives players who struggle to throw splitters an opportunity to capture a similarly moving pitch. Players currently throwing the kick-change include Hayden Birdsong, Andres Munoz, Pablo Lopez, Jack Leiter, Davis Martin, Clay Holmes, Tylor Megill, Griffin Canning, and Grant Holmes. There are lots of variants of this pitch, just like a circle change, so it is incredibly hard to dive deeper into the pitch's viability without a larger sample size; however, I believe it will continue to catch on as the world begins to care more about supinators and pronators.

The Sweeper Era

I like to call our current era of pitching ‘the sweeper era’, with everyone seeming to chase large movement profiles in every direction. It is important to note that sweeper usage is beginning to slightly decline, hinting that teams understand its usage better in 2025. In my recent trip to the MLB Draft Combine, the majority of prep pitchers threw huge sweepers at 10 to 15 inches of movement to their gloveside, some of which were good, and some of which were 22 mph slower than their fastball. The common thought, brought to notoriety by Driveline, is that more horizontal movement increases whiff while decreasing in-zone percentage, thus resulting in less damage from batted balls. While this is true, another important factor in the equation is command. This era is plaguing the non-professional levels of baseball right now, where players are trying to move the ball as much as they physically can without much semblance of the strike zone. In other words, there is a reason the guy throwing bullpens on your X feed is still uncommitted; he can’t throw strikes in game with such large movement spreads.

Sweepers are also one of the easiest pitches to get direct feedback on. When a baseball breaks a bunch from a pitcher's view, the general thought is that it’s a better pitch. I think this is especially notable in pronators, who are only able to access this large glove-side movement by a sharp decline in velocity, which is harder to recognize from the mound. These pitchers might think a pitch shape looks great, but velocity is a clear factor in sweeper success.

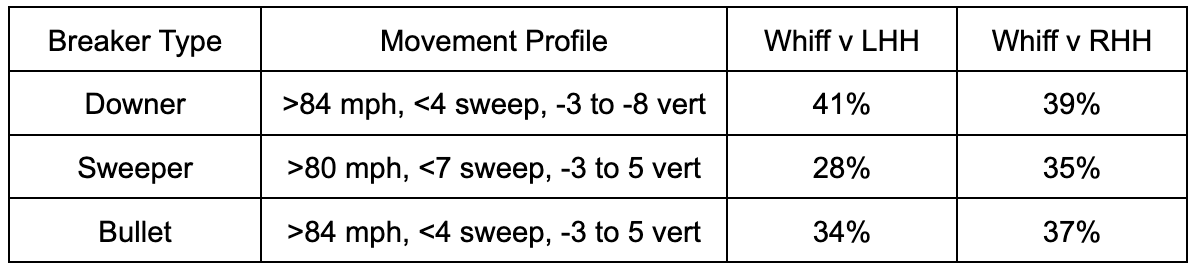

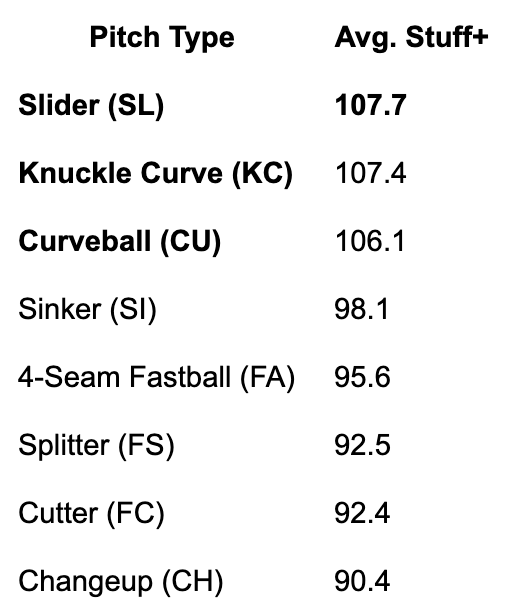

When we train strictly pitch movement, we lose the part of the game that will get you on the field in the first place, command (or, in other words, trust). There is a reason professional pitchers don’t throw giant sweepers from traditional arm slots; they are not a viable movement-velocity tradeoff in today’s game. In Lance Brozdowski’s YouTube video “These 3 Teams are Pitching Innovators”, he notes the correlation between slider movement profiles and their corresponding whiff percentages. The numbers look like this:

RHP Breaker Variation Whiffs:

The results clearly show that the sweeper variation has the lowest whiff% of any slider type, while also being the least ‘platoon neutral’ option, but more on that later. While the sweeper has taken over pitching in the last few years, it is quickly proving to be a one-trick pony that is not for everyone.

In Lance’s video, he referred to the ‘downer’ shaped breaking ball, which typically rides around the 0 horizontal line and gets more vertical movement than a traditional slider, acting as a bridge between a 12-6 curveball and a gyro slider. This pitch was also brought to notoriety a couple of years ago by Tread Athletics, being called the ‘Death Ball’. While the death ball plays along near gyro spin, similar to a slider, it is able to reach bigger levels of vertical movement with key grip and release traits. This pitch has outperformed all other breaking ball shapes in terms of consistent swing and miss when thrown at high velocities (85 and up, typically).

The one drawback of these tighter breaking ball shapes is that if they are not located properly, they have a much higher chance of being hit hard. While the whiff rates are higher on these pitch classifications, the opponent slugging percentage is also higher, which brings us full circle to the ‘command is king’ theory of earlier.

Another perk of this shape of breaking ball is that it is partially accessible to pronators, as they are often able to get gyro spin on their breaking balls. If a player is able to throw a death ball hard enough, it can create a larger ‘pronator's triangle’ than a typical gyro slider. With that being said, there will still be pitchers unable to spin a ball at 85 mph with good depth easily.

After the initial MLB success we saw from the sweeper, I believe we are drawing close to another change within breaking ball shapes in the MLB, moving toward more vertically moving pitches rather than horizontal ones. In my opinion, baseball is the greatest sport to notice trends in. The teams that adopted the sweeper early were rewarded with early successes. The Mets have notably started dipping their toe into the death ball-shaped breaking ball, meaning all of us are already behind on this information. To quote a great man named Ricky Bobby, “If you ain’t first, you’re last”.

The Verty Sweeper

When talking to people about this article, the term ‘verty sweeper’ came up multiple times. This is referring to a shape of sweeper that has less vertical drop than expected, essentially being an even more pronounced east-to-west pitch. As traditional sweeper shapes begin to fade and become less effective, an unnaturally moving sweeper could allow supinators to still gain an advantage with the pitch. The verty sweeper also is generally thrown at higher velocities from lower arm slots than traditional sweepers, allowing it to gain the advantages that faster breaking balls give. We could see more pitchers tighten up their sweeper to make it more horizontal than vertical, which also opens up some more interesting tunneling opportunities.

Seam Effects

While seam effects are a big topic of discussion in pitching, their optimization is spread much thinner. When talking to Lance, he thought that maybe only 7 or 8 teams have actually optimized an objective approach to seam-shifted wake at this point. We know that seam-shifted wake allows for expanded pitch movement patterns, but how do we go about pairing seam effects to players holistically? Sometimes in baseball, when a new trend pops up, teams do not manage it successfully. The Baltimore Orioles earlier in this decade forced sweepers and SSW throughout their system, which, in hindsight, was a poor approach, knowing that both of those trends need to be personalized based on player needs and biases. While we have benchmarks to denote on what pitches seam effects are taking place, there is no public data that can help us further figure out seam effects during ball flight and when they take place. Basically, I want to know the baseball's orientation throughout the nanoseconds of its flight path, to then further research how orientation can be perfected, for lack of a better word. If you’ve ever seen slow-motion video of a pitch being thrown, you can clearly see where seam effects take place during ball flight, but we have no way of further developing these ideas. MLB teams do, and are likely working on that right now. We know what seam-shifted wake is, we have a good idea of seam orientation at release and its uses, but the topic overall has not been studied enough to understand all the relational points with its proper optimization toward individuals.

Platoons and Pitch Nuetrality

I believe the rising popularity of the platoon is one of the most under-represented recent growths in baseball. While platoons have been around for over 100 years, they are at an all-time high in popularity. A large part of platoon popularity coincides with the sweeper revolution, with the sweeper being a staunchly dominant pitch in same-handed matchups, and a fairly poor offering in opposite-handed matchups. Because so many pitchers now rely on sweepers to be their ‘out pitch’, we have seen coaches deploy more platoon hitters in lineups than ever before, in a strategic sense.

Without doing much prior research on the topic, I would have assumed switch-hitting had remained steady over the years, but I couldn’t be more wrong. Switch-hitting is at an all-time low, with less than 10% of today’s batters being switch-hitters, down from over 20% decades ago.

Platoon research has been a thing for a while, but it really started coming to late in the late 2010’s led by The Hardball Times. Initial research looked like this, simply showing the run value of different pitches in handedness matchups, and then was continued with positional platoon summaries.

Max Marchi of The Hardball Times released some of the first advanced pitch type versus platoon matchup research in 2010. He used multilevel modeling to figure out the run value of pitches, something that still holds up today, with some pitch classification differences.

The pitches at the top of this value sheet are the least ‘platoon neutral’, whereas the ones at the bottom are the most platoon neutral. In general, any pitch that moves vertically is equally valuable against righties and lefties. With the classifications of curveballs, I think it’s important to note we don’t exactly know what the run value for a pitch like the death ball would be in today’s game. If I had to guess, it would be up there as the most platoon-neutral pitch alongside gyro sliders and vertical changeup variations like kick-changes and splitters.

So, with all of this information, what can neutralize a platoon in today’s game and the future? The answer is more pitches and more vertical shapes. That is not to say sweepers are not still a beneficial pitch, but if I had to pick 3 pitches to use in today’s game, the sweeper would not be one of them. In an ideal world, a pitcher has four valuable pitches against both sides of the plate, with another option that they can mix in. Realistically, this would mean having a 6-pitch mix for a starter if our example includes typical pitch shapes. Having a high-velocity fastball or a hard downer breaking ball allows for guys to have fewer pitches, since they are some of the only truly platoon-neutral pitches.

In a landscape where we see guys with completely different arsenals to both sides of the plate, platoon neutral pitches help bridge the gap and make pitchers have more complete arsenals without having to learn extra pitches.

Pitch Decay

A large part of the argument to simply expand starting pitchers' arsenals is the concept of pitch decay, which has been heavily covered by Lance Brozdowski as well. To keep it simple, the more times a batter sees a pitcher, the better they get against them. Every offensive hitter metric jumps a small amount between plate appearances, except for between the 3rd and 4th PA, when those metrics decrease, because typically only the best pitchers in baseball make it to the order a fourth time.

When talking to teammates during college games, I would often hear them have their ‘lightbulb moment’ with opposing pitchers after their first or second PA, finally understanding how a pitcher is trying to attack them and then making that adjustment.

This is where an arsenal’s depth comes into play. Let’s say you’re a right-handed pitcher who has a cutter primarily to get lefties out, but you throw it sparingly to righties. Maybe, during your third time through the order, you move toward primarily throwing cutters to right-handed batters instead of your usual fastball. While your stuff grade will decrease slightly due to throwing a cutter to a same-handed batter, you would likely nullify the effects of pitch decay, thus giving the pitcher an advantage still, despite going through the order a third time. This is only really an available option to pitchers with 5+ pitches in their arsenal, but is a distinct leg-up to those that can command a handful of offerings.

This concept can help reverse the trend of relievers entering games earlier, improving team outcomes and pitcher statistics; however, as previously discussed, a 5 pitch arsenal is only available to certain types of pitchers.

Pitch Decay by Pitch Type

My next study will likely be on pitch decay, and attempting to figure out which pitches decay quicker than others in a full-fledged research project. For now, let’s take a look at the top ten pitchers by innings pitched to see if we can find any preliminary information that can point us in the right direction. When looking at this group of pitchers, two clear categories emerge: lower-slot stuff guys and deep arsenal non-stuff guys. These categories make sense because we’ve already talked about how they can both succeed, but the most interesting thing about this whole group is how little they throw four-seam fastballs. The majority of these pitchers throw alternative fastballs (cutters, sinkers, and splinkers) at a high rate. Given how rarely this group throws four-seamers, our sneak peek at pitch decay by pitch type suggests that four-seamers decay at a faster rate than other pitches, likely because of their usage and one-plane shape.

The Catcher Perspective

The catcher angle is an important one to consider in this conversation, and it will be a large part of my next study on pitch decay. Catchers have the toughest job in baseball, and the toll catching puts on someone's body is an important thing to note. While developing with the bat, there has become an increased demand for catchers to be as good as possible with their receiving and defensive capabilities nowadays. With how many data points are now available on catchers, their defensive development has become a focal point of teams during this decade. On top of all of that, though, catchers also have to call pitches. This can sometimes get lost in the shuffle, because catchers aren’t the ones dinged for calling bad pitches, pitchers are. When talking to Lance, organizations have their own internal measurements for pitch calling by catchers, but it's hard for us on the outside to get a well-rounded view of who the best pitch callers are in the MLB. Lance also brought up a very important question, asking how analytics departments can get buy-in from a catcher to spend more time on optimizing their pitch calling.

The catcher's perspective is important because they have the opportunity to pair analytics with the actual product on the field. A good example to explain this would be when a pitcher throws a backed-up slider but still gets a whiff. That individual pitches stuff and location scores would be bad, but if a catcher has the knowledge to read a player's swing tendencies and call that ‘bad’ pitch, it can still get good results. Catchers could also be at the forefront of pitch decay research, with most of them already knowing how each pitcher is affected deeper in games, and how to negate pitch decay by calling the right pitches. If we know orgs have models that show them who their best pitch callers are, our answer to a lot of these questions lies within what makes some catchers better at pitch calling than others.

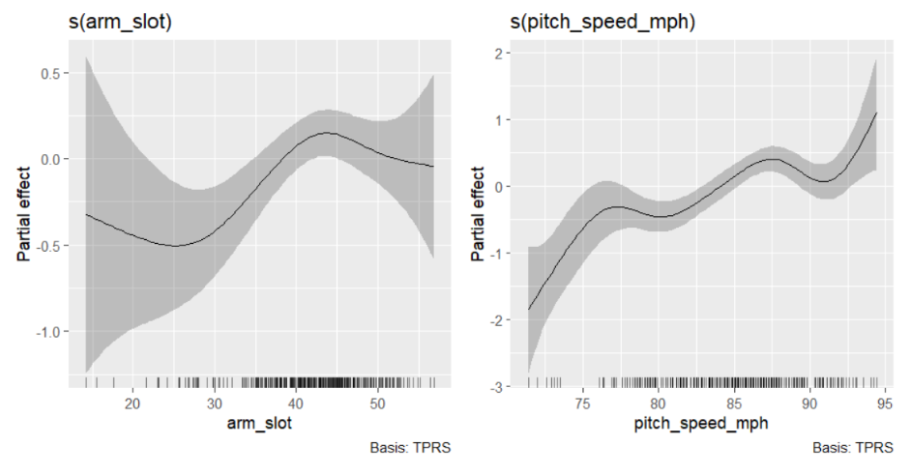

Arm Angles and Health

When predicting the future of pitching, arm angles are already at the forefront of baseball thought. Over the past few years, numerous studies have come out citing that higher arm angles can increase the risk of injury and put more strain on the elbow. Arm angles are not all created equal and have a lot to do with biomechanics and other pitching functions, but we have seen teams and players begin to make subtle adjustments to their arm angles. The average MLB arm angle is currently 39 degrees. In 2025, we have seen aces like Max Fried and Garrett Crochet lower their arm angle in alignment with this new arm health research, albeit the adjustments have only been by a few degrees. Some research cites that arm angles above 30 degrees cause an increase in torque on the elbow, with that torque building between 30 degrees and 45 degrees, where a large majority of MLB pitchers reside. However, there is recent contrasting research that claims arm angle has no effect on the increased risk of UCL damage.

In the case of contrasting research, I typically won’t pick a side, but in my playing experience, I did notice I was more injury-prone when throwing from a higher slot. I notably dropped my slot significantly in my senior year, and was able to pitch without elbow pain. If a guy like Garrett Crochet is dropping his slow significantly after an immaculate 2024, then it is fair to infer the change was not performance-based but rather health-based. Arm angles continue to drop every year to new all-time lows, proving that this is more than just a trend in the league.

Since it appears as if teams are buying into this new research with their young pitchers, this feels like a perfect time to note that there are advantages and disadvantages to having a lower arm angle. First off, the health part needs to be monitored as more research comes forth. Secondly, there are more pitch shapes available to players who throw from an average or lower slot. It is far easier to get horizontal movement on your pitches from a 35-degree arm angle compared to a 55-degree arm angle, which thus opens up all four quadrants on a movement plot.

Despite my initial thought that lower slot guys would have more elite breaking balls, the research shows different. Players are more likely to have 2 elite breakers from an average or slightly above average slot compared to a lower-than-average slot. Relievers are bringing down the average arm angle in baseball, whereas starters tend to range on the higher side of the spectrum.

Let’s take a look at Trey Yesavage, who will throw from one of the highest arm angles when he makes his MLB debut. Courtesy of TJStats, Yesavage throws from a 72-degree arm angle and throws nearly all of his pitches in the upper right-hand quadrant, which is nuts.

This is a good example of how arm angle can limit your pitch movement, but that doesn’t mean super high arm angles are only a bad thing. Trey Yesavage is an excellent pitcher and should have a fruitful MLB career as a mid-rotation starter. The best thing about him? He’s different. He throws in such a ‘funky’ way that deception and atypical movement will keep hitters confused despite his minimal movement separation. While there could be inherent risk to throwing from this armslot based on some people’s views, the truth is that injury risk can never be fully mitigated, and Yesavage is at a distinct advantage with his current mechanical processes. In general, I expect players with higher arm slots to become even more sought after as pitchers consider dropping lower, and unique looks become rarer.

Deception is something that is extremely hard to measure with numbers, and is instead typically measured through hitters' perspectives when facing a pitcher. The Rays, however, are on the cutting edge of deception research, measuring frame rate and how long it takes to see the ball from the hitter's view in order to try and quantify deception. This is something some organizations may have, but others are likely lagging behind in.

When considering injury risk, in this era of pitching, everyone is chasing velocity. Higher velocities inherently increase injury risk, and we often forget about that. Higher velocities increase strain on the elbow, which has been shown in countless studies. In simple terms, according to Dr. Gene Coleman in a 2024 story, “Research and reports by members of several MLB Teams indicate that the recent emphasis on pitching velocity has had negative effects on the health, safety, and performance of players at all positions, not just pitchers.” While there are many ways to look at the topic of velocity, let’s not pretend that arm angles are the leading reason for injury; they may just be one of many factors.

The Future of Pitching

With all of this information and research, one thing sticks out in my mind: the ability to be different than others is the greatest ability in pitching. Whether that means throwing from a unique arm slot or throwing 7 pitches, being different is a separator at the next level if you don’t have elite stuff. If you want to consider what teams are likely looking toward in the future, though, everything I have seen points toward deceptive supinators being of an even higher priority than they are now.

While it isn’t a large difference, players with lower arm slots have better overall Stuff+ scores as well as more pitches in an arsenal on average. The degree when stuff and arsenal options begin to ‘drop off’ is around a 40-degree arm angle, with another dropoff in arsenal options occurring around 52 degrees, despite an uptick in stuff in that same range. There are good stuff options available at most arm slots outside of those that are abnormally high, but this is where stuff measurements tend to fail because deception is not baked into them.

Knowing that you can develop two plus breaking balls from almost any slot if you’re a supinator, you really just need to develop at least 2 more pitches on the other side of the 0 line. From a lower slot, you have options to work 4-seam fastball angles up in the zone with VAA, while also implementing a second fastball in a cutter or sinker. The changeup variation will always be the toughest from a lower slot, but with variations like the kick change available from lower slots as well, there should be a way for nearly everyone to throw offspeed from these angles.

In the pitch plot above, you can see what I think the future of pitching might look like. 5-6 pitches, multiple fastballs, a changeup variant, a horizontal slider, all capped off with a downer curveball/slider/death ball. With this deep of a pitch mix, you have four legitimate options against both sides of the plate, while still leaving room for surprise pitches to negate pitch decay. All of this from a low-ish arm angle around 35 degrees, from a natural supinator, is a dangerous pitcher. If command is an issue, utilizing a sinker to same-handed hitters and a cutter to opposite-handed ones is a prime way to retain control of the zone while avoiding too many 4-seam fastballs.

As previously mentioned, the 4 seam fastball is dying, despite people starting to utilize its shape in better ways. More pitchers will start moving away from the four-seam fastball as their primary pitch in the coming years, especially right-handed pitchers. Elite 4-seamers from the left side might still hold some ground, but even then, the best fastball being used as a 1A or 1B pitch aligns with the new trend of increasing breaking ball usage.

In the case of recent Mariners draftee Kade Anderson, he uses his 4-seam fastball to set up all of his other pitches. He throws his fastball in the zone less than his breaking balls, something that is extremely rare to see in baseball. He typically throws his fastball up and away to righties, which helps set up his slider, curveball, and changeup lower in the zone. It clearly worked in college, and this type of pitching is something we could see more of from guys without elite 4-seamers.

The future of pitching relies on more than just pitches, though. I have a strong feeling that deception will soon become a priority for MLB teams. This past year, we have seen guys like Jackson Jobe have hiccups in their strikeout development despite having plus stuff. Jobe falls into the category of ‘the most average right-handed look on the mound’ when looking at his mechanics. Jobe uses his lower half well on the mound, but the arm climbs significantly at delivery, negating any possible VAA fastball effects from getting into his legs. There is very little deception in Jobe’s delivery, with his good stuff playing down slightly as a result.

It’s very hard to teach deception, and it’s not something everyone is going to be capable of; however, I believe teams are going to start prioritizing deceptive deliveries since it raises the floor of a player. Your stuff plays up, you get more whiffs, and in turn get more outs with a deceptive delivery. Whether that means hiding the ball well or coming at the hitter from abstract angles, I believe this is something teams are beginning to key in on more than ever.

Another point to make when talking about the future of pitching is that the low-velocity pronator is a dying breed. An extreme example of this is Kyle Hendricks, but guys like Patrick Corbin, Eduardo Rodriguez, and Bryce Elder are quickly being phased out of baseball. Without any options to obtain a plus arsenal from low-velo pronator’s, the game is passing this brand of pitcher quickly.

The Hitter vs Pitcher Perspective

The hitter's perspective is an important one in this discussion. We have seen hitters tailor their swings in the modern era to cover the plate very well, attempting to keep their barrel in the zone for as long as they can. This type of swing change is geared toward covering as much of the zone as possible, which tailors toward hitting horizontally moving pitches first and foremost.

I think we’ve overcomplicated this idea slightly, because we are in a world where there are very few pitchers who throw breaking balls in a downer shape. Is it not a good idea to zig when everyone else zags? While reaching this pitch shape takes a lot of work, all data points toward this pitch being incredibly successful against both righties and lefties, as seen in the previous chart detailing whiff rates by breaker shape.

As arsenals expand horizontally, walks and strikeouts will go up, and home runs will also increase as pitchers get into more disadvantageous counts. Home runs will also continue to rise because of hitters' approach, with lift and pull approaches taking over MLB while being highly effective against secondaries that are bound to be hung.

I anticipate that this trend for hitters won’t stick forever, though. Since stuff is the priority for pitchers, I anticipate hitters will become more passive in the coming years and counter with a more contact-focused approach. While chicks dig the long ball, baseball is still a cat and mouse game, and when one side changes, the other is forced to make a counter move. If that change happens, we could see pitchers go back to a control and craft focus, but don’t let me get too far ahead of myself.

I think it is very likely that we see an uptick in switch-hitter value in the coming years as well. With switch hitters being at an all-time premium, they essentially take the spot of two people on a roster that loves platoon advantages. Until pitchers become more platoon-neutral, both switch hitters and ‘even’ split hitters will continue to rise in value, while average righties continue to decrease in value.

If pitchers do trend toward becoming more platoon-neutral in their pitch arsenal, we could see teams pivot to tailoring their lineup toward their home ballpark advantages or the current league run environment even more than we’re typically seeing.

TLDR / Notebook Recap:

-Average to low-slot supinators are the future and easiest development model for a combination of stuff, arsenal completeness, and possibly health.

-Using good 4-seam fastballs as a secondary or shared primary pitch, especially to opposite-handed hitters.

-Recognizing pitch decay and switching pitch usage tendencies, the 3rd time through the order holds a lot of value. There is over a 50-point difference in hitter xSLG between their first AB and third. Arsenal expansion makes this easier.

-Deception is becoming a larger competitive advantage in a game where everybody is really good and getting better. Measurement of deception is still in its infancy.

-Platoons are more popular than ever, increasing the need for platoon-neutral pitches like downer breaking balls, vertical offspeeds, and ride fastballs.

-Sweepers are on the out, offspeed is gaining traction again.

-A 5+ pitch arsenal helps defend against pitch decay and platoon advantages.

-A 5+ pitch arsenal will be more accessible when seam effects are fully researched.

-The best pitchers tend to throw more pitches than average.

-There is no clear correlation between arsenal depth and production right now.

When doing some research for this project, someone pointed me in the direction of Paradigm Player Development, who wrote this article noting changes in college pitch usage last year. While it does not directly correlate to this study, there is an overlap in some points. They did a great job of explaining the statistics behind changes made in the college pitching game last year. I would recommend checking that article out here and following what they're doing on X @ParadigmPDS.

Discussion